September 11, 2001 changed things for Francisco Rivera. How he understood himself changed. How he understood his commitment to his family, his community, and his country changed.

“When I think about that day, it’s as vivid to me as what I did this morning,” he says. “I remember every detail — where I was, what I was doing. I can map every moment. So, it doesn’t feel like it was 20 years ago at all. I may have aged 20 years, but in my mind … it’s like I’m stuck in time.”

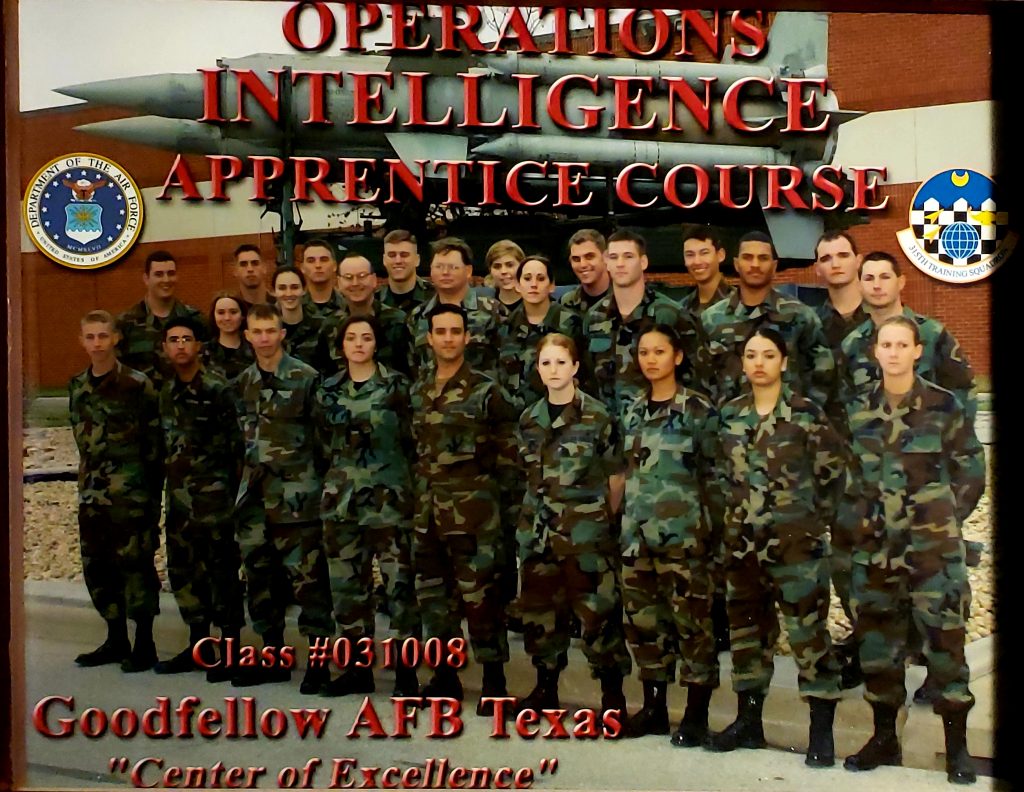

The son of an aircraft mechanic and crew chief who served in the Strategic Air Command, and the grandson of a soldier who served in the United States Army, Francisco belongs to a rich legacy of “service before self.” When it became clear to him that the United States was going to war, he knew right away what he would do. On March 21, 2003, his birthday, he enlisted in the United States Air Force.

Francisco is proud of his service. He developed targeting products to support strike operations down range, and he stood up intelligence training programs for units conducting close support operations. His work mattered.

When he left active duty in 2009, Francisco chose to continue his service as a civilian for the Air Force and now Navy. Currently, he’s responsible for training the next generation of Joint Targeting Professionals and it’s hard, he says, not to see himself in his proteges.

“I feel protective of them,” he says, “but — because they’re encountering so many of the same issues I’ve encountered — I’m able to guide them. I can pass my experience and knowledge on to them.”

“Some of these troops were in kindergarten when September 11 happened,” Francisco reflects. “It’s a reality check. A bit jarring. I know they’re young, but I don’t think about it until they remind me.”

Francisco has watched Airmen he’s trained to support the same operations he once supported. He has seen himself in their faces. “When I watch them,” he says, “I’m proud. But there’s a bitter-sweetness in it. Until recently, I never really thought about them being ‘the next generation fighting the war.’”

When he talks about what withdrawal from Afghanistan means for service members, Francisco gets emotional. “The Global War on Terrorism isn’t just something I did, it’s part of who I am. So, when something that’s been a part of you dies, it feels like a part of you dies,” he says.

“Of course,” he goes on, “When this conflict is over, awareness will naturally fade. As awareness fades, our national memory of the fight that took place, and those who fought it, will fade.”

That concern — that civilians will forget service members now, in their deepest moments of self-reflection — is what has driven Francisco’s support of the national Global War on Terrorism Memorial.

“The GWOT Memorial will cement the Global War on Terrorism as a generational conflict on par with others that have already been memorialized,” he says. “If this were done at any other time and in any other way, it would send a message to those of us who’ve served that our service was somehow … less.”

In this Memorial, Francisco sees deeper meaning and a bigger opportunity for his civilian friends and neighbors. “I look across the country today, and I wish that civilians could understand that brief moment of unity we felt in the early stages of this conflict. With the GWOT Memorial, we have the opportunity to again share that kind of deep togetherness. That did happen, and I believe that it can happen again.”